Latest News

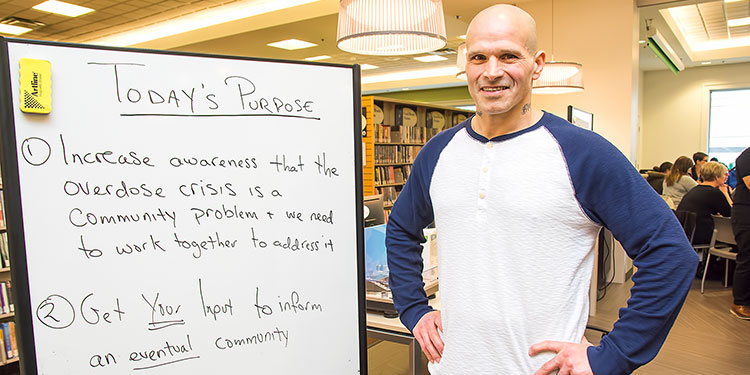

Learning about the power of compassion, empathy

Published 10:51 PST, Tue March 6, 2018

Guy Felicella remembers the day his life

changed.

After telling him about living with

depression, her black days, community worker Liz Moss said, “Do you feel black?”

“I will never forget it. It was like the sky

parted and I looked up and I just said, ‘yeah,’”

Now educating school children, health

professionals and the general public while working as a community liaison

officer for Downtown Eastside Connections, Felicella talks of his teaching

method.

“I think with addiction, you have to attach a

story to it. You have to have more understanding instead of just a judgement

call.”

Felicella’s story started ordinarily enough.

He grew up in Steveston, went to St. Paul’s and James McKinney for elementary

school, then to Boyd and London for junior secondary school.

“I played West Richmond soccer for 15 years.

I played baseball. I was just an everyday average day kid—middle class—growing

up in Richmond. I wasn’t like a person you’d think would do drugs. The last

place anybody every thought they’d see me was the Downtown Eastside.”

But, by adolescence, he couldn’t stop the

pain from years of verbal and physical abuse.

“When you‘re dealing with pain you just want

to get rid of it as fast as possible,” Felicella says.

“The first drug I ever smoked was pot. It was

the answer for me at 12. And then at 16 it was cocaine. And then, right after

it was heroin. Obviously for me, the weed wasn’t stopping the pain; coke wasn’t

stopping any pain. When I found heroin the answer hit me.”

For decades, living on the streets, stealing

to support a $300-to-$400-a-day habit, heroin was the answer, and the only

answer, to Felicella’s pain, until the day he had that fateful conversation

with worker Liz Moss at Vancouver Coastal Health’s Insite, safe injection,

Centre in the Downtown Eastside.

Her compassion reached his heart and started

Felicella on the path to a new life, away from self-hatred, street drug use,

and most of all, away from pain.

Felicella was given clean, safe drugs to

substitute the expensive, dirty ones he’d been using. The street drugs were

dirty not only in their lack of medicinal purity but in their sterility. Once

again, practical compassion saved not only Felicella’s life but his leg.

“I had life-threatening osteomyelitis from

dirty drugs. Four or five times they wanted to amputate my left leg so now I

walk with a limp but at CTCT in Downtown East Side (The Community Transitional

Care Team, a residential acute care clinic in the Downtown East Side), you

could use while living at the facility while you got antibiotics. One of the

reasons I have a left leg is their accepting me, reducing harm, not looking and

judging.”

According to one substance user’s mom,

infections from illegal drugs continue to be a big problem.

She says hallways at St. Paul’s Hospital are

filled each morning with injection drug users sitting in chairs receiving their

scheduled daily intravenous antibiotic treatments to deal with the aftermath—horrendous

skin lesions, systemic infections—of dirty drugs.

Pharmaceutical grade drugs have to pass

rigorous health and cleanliness standards. Street drugs don’t. Dirty drugs cost

taxpayers many health dollars. Clean, legal drugs save money.

After the fateful day Liz Moss reached out to

Felicella, the day her compassion hit home and the day when there were useful

options in place for him, Felicella opted for opiate assistive therapy where

clean, safe drugs are provided by the health care system to help people

stabilize their physical and mental health.

“What opiate assistive therapies do is they

address the physical need to stabilize the person using substances,” he says. “Once

the physical dependence gets addressed, so the person isn’t so hell bent on

getting drugs, they can start piecing their life back together.”

And piece it back together, he did.

“I was on opiate assistance therapy which

addressed my physical dependency. It actually frees up the mind on learning new

ways to cope. I started to talk about it with people.”

And how did that learning to cope come about?

“We all come to a point in our life where we

have to trim off a little bit of the pain. Don’t try to look at it all. Just

try to look at what you can do. Just trim it off bit by bit and when you can’t

handle it, stay on your opioid assistance therapy.”

Today, with a job, home and two children to

bring even more joy into his life, Felicella works at a clinic that offers free

drop-in treatment services for those with substance use and other issues.

It offers opioid substitution therapy as well

as providing take-home naloxone kits, peer support, and the services of on-site

nurses, social workers, financial liaison, and community workers.

Physicians and pharmacists are also available

to give clients medication for conditions such as HIV, hepatitis C, and

psychiatric illnesses.

Felicella also freelances as a speaker in

elementary and high schools, teaching children and teachers alike that a middle

class life is no armour against drug addiction. He speaks of his journey,

teaching compassion, teaching hope.

Felicella speaks of the need for ongoing care

and support, so that people leaving substance abuse can lead healthier lives.

“If you can just get away from street drugs,

the first 3 months are just such a battle in itself. What happens to your

clients when they finish your treatment? We need a transitional facility where

people can go and live afterwards, learning life skills, jobs, get jobs through

this, find housing, all these things.”

A house in Richmond’s Woodwards district is

home to a transition house for women, women who are putting their lives back

together now that they are clean and sober. Many more such ordinary-looking

houses, where people can build on the healthy lives they’ve started, are

needed.

Felicella says that until society changes its

attitude, the costs associated with street drug use will continue and middle

class kids will continue to overdose on drugs that contain unexpected lethal

additives like

Fentanyl. People do what it takes to find the

hundreds of dollars every day to get the drugs they need to numb their pain.

Felicella teaches that anyone who has had a

break-in or a theft from their car has been touched by the high price of

illegal street drugs.

“Substance abuse not only impacts the person

using it,” says Felicella. He speaks of the kids from good homes ending up in

the Downtown Eastside, of the families devastated by overdoses, and of the need

for practical compassion: “You can’t save a dead addict.”

Today, Felicella sees an additional benefit

in his new life: “I have two beautiful children. Without all the help, without

the opiate assistive therapy, my son wouldn’t have been born my daughter wouldn’t

have been born.”

He cautions against teaching with a

one-size-fits-all approach: “We’re all unique individuals, what may work for

some may not work for others.”

But he says that, for him, opiate assistive

therapy was vital, that and Liz Moss’s kindness.

What does he want the students and adults he

speaks with to learn?

“Show a bit more compassion and empathy

towards people who are really struggling. That’s what really wins it over in

the end,” Felicella says, “I would not be here today without it.”